The last months of the existence of the ADR were accompanied by a serious worsening of its international position, and acute military and political crisis in the republic. The rapid success of the Red Army in the fight against Denikin and further retreat of his troops to the South (to Rostov-on-Don) has led to greater diplomatic pressure from the leaders of Russia on Azerbaijan. January 2, 1920, the People’s Commissar for Foreign Affairs of the RSFSR Georgy Vasilyevich Chicherin sent a note to the Government of Azerbaijan with a proposal “to conclude a military agreement between the two military commands with the aim to finish off the White Guard Army in southern Russia” (1). For Azerbaijan, this actually meant entering the war against Denikin. Minister of Foreign Affairs of ADR Fatali Khan Khoyski in his note dated January 14, evaluated Chicherin’s proposal as “interference in the struggle of the Russian people in building their domestic affairs”, but also expressed his readiness “to establish good-neighbourly relations between the Azerbaijani and Russian peoples”. (2)

On the other hand, this situation has played into the hands of the Azerbaijani politicians. The march of the Bolsheviks towards the Caucasus and the Entente’s concern regarding their entry into the alliance with the Turks, has led to the Supreme War Council in Versailles (at the initiative of the United Kingdom) de facto recognizing the Government of Azerbaijan in January 11, 1920 (3). The next item on the agenda was the issue of security and defense of Azerbaijan. The outcome of lengthy negotiations between the members of the Entente, also attended by the Azerbaijani delegation, was a decision taken by the Supreme War Council on January 19, 1920, in opposition to the opinion of a number of military experts who insisted on sending not only weapons, but also the soldiers to Georgia and Azerbaijan. British Prime Minister Lloyd George, who did not want to confront the Bolsheviks directly, “found it necessary to assist the Transcaucasian republics in the form of weapons, equipment and uniforms. As for sending troops to Azerbaijan and Georgia, he recognized the impossibility of doing so. He believed that the Caucasian republics should strengthen their defenses and especially the defensive capability of Baku, by their own armed forces”. (4)

The main condition for the speedy delivery of arms to the Transcaucasian republics was the settlement of territorial disputes between Georgia, Armenia and Azerbaijan (the issue of Batumi, the issue of the Armenian-Azerbaijani, Armenian-Turkish border and so on), which hindered the process of providing assistance promised by the Allies. They clearly pointed out that “the republics of Transcaucasia can be helped only if lasting peace and mutual understanding will prevail between them” (5). Consensus between the Transcaucasian republics on the issues listed above has never been achieved. This was one of the factors that precipitated the fall of the ADR.

The main condition for the speedy delivery of arms to the Transcaucasian republics was the settlement of territorial disputes between Georgia, Armenia and Azerbaijan (the issue of Batumi, the issue of the Armenian-Azerbaijani, Armenian-Turkish border and so on), which hindered the process of providing assistance promised by the Allies. They clearly pointed out that “the republics of Transcaucasia can be helped only if lasting peace and mutual understanding will prevail between them” (5). Consensus between the Transcaucasian republics on the issues listed above has never been achieved. This was one of the factors that precipitated the fall of the ADR.

Meanwhile, on January 23, 1920, after de facto recognition of Azerbaijan, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the ADR received the following note from Chicherin, where he pointed out that his note has received no response from the government” (6), to which Foreign Minister of the ADR Khoyski in his reply note dated February 1, stated that the establishment of relations can happen only on the basis of the sovereignty of both sides” (7), thereby insisting on recognition of Azerbaijan’s independence. Russia’s diplomatic activity in those days can be explained by its political and economic interests in Azerbaijan. If the political interest of the Bolsheviks was the establishment of Soviet power in the South Caucasus and its further advance to the East, then the economic one was determined by the desire to gain control of the Baku oil with the aim to revive the post-war economy of the Soviet state. Proof of that can be found in Lenin’s telegram of March 17, 1920, “Taking Baku is very, very essential for us. Direct all efforts towards that…” (8). It’s fair to say that the oil factor played a key role not only in Russian politics, but also of other countries that were in foreign relations with Azerbaijan. The Azerbaijani government has tried to make the most of this circumstance, wanting to acquire the necessary weapons and goods for themselves (9). The desire to gain recognition by Russia was dictated primarily by the desire of the Government of Azerbaijan to establish trade and economic relations with it, which in turn has been very important for the revival of the oil industry of Azerbaijan, the decline of which led to the economic crisis in the country.

A serious foreign policy blow that complicated the situation in Azerbaijan was being left without support from the British in the fight against the Bolsheviks. In the beginning of March, reaching an agreement with Bolsheviks not to enter into an alliance with the Young Turks (an agreement with the “Karakol” organization in January 1920 was denounced), the British promised not to interfere in the policy of the Bolsheviks in the Caucasus (it also was the beginning of trade and economic relations with Soviet Russia) (10).

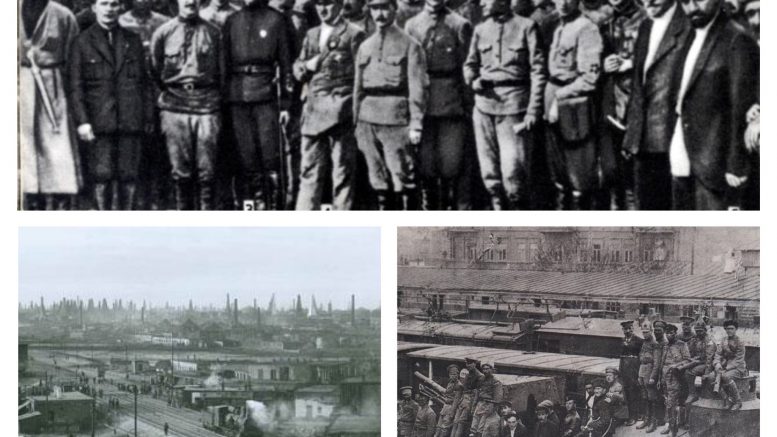

The domestic political situation in Azerbaijan has also continued to deteriorate. In March 1920, an Armenian revolt broke out in Karabakh (11). The goal was to seize Askeran, Shusha and Khankendi to further connect with Zangezur Armenians. To prevent this attempt, the Government of Azerbaijan, in order to maintain the combat capability of units of the national army, was compelled to redeploy additional forces to the west (along with Karabakh, fighting has been going on also in Ganja, Gazakh, and Tovuz). Despite the successes of the national army in Karabakh, the government realized that it did not have the strength to fight both the Armenians and the Bolsheviks, so an attempt was made to stop the fighting through negotiations, but the negotiations that took place in Tbilisi did not yield any results (12). This situation was closely followed by the Bolsheviks. Using the moment to their advantage, they began to concentrate their forces on the Azerbaijani border. Khoyski wrote about it in his note to Chicherin dated April 15, “there is a concentration of significant military forces of the Russian Soviet government in the Derbent District, at the borders of the Republic of Azerbaijan …” (13). On April 21, the commander of the Caucasus Front Tukhachevsky has issued guidance to the command of the 11th Army and Volga-Caspian Military Flotilla to attack Baku: “The main forces of Azerbaijan are occupied on the western border of the state. In the area of Yalama – Baku station, according to intelligence sources, there are only minor Azerbaijani forces”, “The Army Commander of the 11th Army, April 27 this year, cross the border of Azerbaijan and capture the territory of Baku province by rapid advance. Complete the Yalama – Baku operation in 5-day period” (14).

The threat of Soviet intervention was the cause of worsening of the government crisis, which ultimately led to its downfall. The statements made by Khoyski and his supporters on holding a radical course in domestic policy, dissolution of the parliament and granting extraordinary authority to the government met with resistance of supporters of soft policy towards the Soviets (represented by the parties of Ittihad, Adalat, Socialists, and Ahrar), led by M. H. Hajinski. Had received the mandate to form a new government, Hajinski not only prolonged its formation, but attempted through negotiations to attract members of the Communist Party of Azerbaijan into the ranks of a new government (15). But they not only did not think of taking this offer, but on the contrary actively armed and coordinated their actions with the Bolsheviks. (16)

Azerbaijan was let down by the liberation struggle of Turkish nationalists (Kemalists) gaining momentum in Anatolia, who were in a difficult situation and needed serious financial and military support. This pushed them towards an alliance with the Bolsheviks. In his letter to Lenin dated April 26, 1920, Mustafa Kemal Ataturk pledged to “make the Republic of Azerbaijan to enter the circle of the Soviet state” (17). In return for this, he demanded “5 million Turkish liras worth of gold aid as well as weapons and ammunition…” (18). Thus the Bolsheviks, under the guise of helping the Turks in Anatolia, had a formal excuse to invade Azerbaijan (in spite of a secret military convention on military assistance in case of an attack, which was signed with Turkey on April 15, 1920). Georgia, which was considered by the Government of Azerbaijan as a natural ally in the fight against the Bolsheviks, with which it had concluded a military alliance in the summer 1919, also failed to provide an expected assistance. Having made a deal with the Bolsheviks, Georgian politicians have entered into a cooperation agreement with them in exchange for recognition of their independence by Russia (19). It is worth highlighting that this idea was not new to the Georgian politicians. Such statements have taken place also during their negotiations with the Entente (20). Thus, deprived of both internal and external protection, the state created with the enormous efforts made by the Azerbaijani intelligentsia, faced the imminent threat of occupation. In April 1920, a plan to seize Azerbaijan has entered its final stage.

On the morning of April 27, the communist armed forces began to occupy critical infrastructure in Baku, railway station, post office, telegraph, radio, police stations, major oilfields and industrial enterprises, military and commercial ports, etc. Telephone and telegraph communication between Baku, northern border and Ganja have been disabled (21). An elite police regiment “Yardim alayi” (a reserve regiment within a 5000-strong Baku garrison, which was under the influence of the Bolsheviks; the garrison’s inaction greatly facilitated the capture of Baku), entrusted with the task of protecting of Parliament and other public institutions, consisting exclusively of the Turks, also sided with the Bolsheviks (22). With help of Turkish soldiers the military governor of the city General M.G. Tlehas was arrested (23). In parallel, the same day, April 27, at 00:05, the “III International” armored train (with A. Mikoyan, G. Jabiyev and G. Musabekov on board) crossed the Samur Bridge and, overcoming the resistance of a few units of the Azerbaijani army, rushed to Baku. Attempts to stop the advance of the armored train, first at Yalama station and then at the station of Khudat, Khachmaz, Khirdalan have failed. April 27, at 11 pm, the Bilajari station was occupied. At four o’clock in the morning the “III International” armored train arrived at Baku station (24). At 16:00, the Russian army, the Central Committee of the All-Union Communist Party (bolsheviks) and the Baku Office of the Caucasian Regional Committee issued an ultimatum to the Azerbaijani parliament demanding to surrender power. The same ultimatum signed by the commander of the Azerbaijani Red Fleet (consisting of pro-Bolshevik-minded sailors) was presented to the Government and Parliament of Azerbaijan by Chingiz Yıldırımov (25). In his speech at the extraordinary session of parliament Mammad Amin Rasulzadeh described the ultimatum in the following terms: “Hiding behind the idea of helping Anatolia, this occupation army has come and will never walk out of here. Accepting this ultimatum and surrendering to the Bolsheviks is completely unnecessary. We reject the ultimatum with disgust”. Despite the protests of Rasulzadeh and Shafi Bey Rustambeyov, at 23.00 the Parliament adopted a decision on the peaceful transfer of power to the Bolsheviks (26). The Military Revolutionary Committee, established on April 28, 1920 under the chairmanship of N. Narimanov, proclaimed the Azerbaijan Soviet Republic, and the next day, the same body in its official radio address, called for military aid from the RSFSR (27).

On April 30, the main units of the XI Army entered the city. In the course of their advancement, a group of Turkish officers led by Halil Pasha gave them active support, which agitated among the local population with calls not to resist the Red Army (28). The Russian leadership has managed to realize its main strategic goal in Azerbaijan. On April 29, 1920, Lenin, in his speech at the All-Russian Congress of Workers of glass porcelain production noted: “Also yesterday, we had received the news from Baku, which indicates that the position of Soviet Russia is headed for the best; we know that our industry is standing with no fuel, and now we received the news that the Baku proletariat has taken power into their own hands and overthrew the Azerbaijani government. This means that we now have such an economic base that can revitalize our entire industry” (29). Such a rapid and almost bloodless introduction of Soviet troops in Baku was the result of a well thought out foreign policy of the Russian leadership, which managed to neutralize the external allies of Azerbaijan. The important role has been played by internal turmoil spread throughout Azerbaijan as a result of the Armenian uprising in Karabakh and by the position of the majority of political parties in Azerbaijan in relation to Russia. The lack of national consciousness among the wide population was also an aggravating circumstance for supporters of Azerbaijan’s independence. Given the limited resources of national intelligence to lead the struggle for independence, we can say that loss of the opportunity to maneuver between the global and regional actors in international politics due to existing contradictions between them and being in absolute external and internal insulation, has made the occupation of Azerbaijan by Soviet Russia possible.

Used sources:

- A radio telegram People’s Commissar for Foreign Affairs Chicherin to the Ministry for Foreign Affairs and the Azerbaijani people. . 06.01.1920. National Archives of the Republic of Azerbaijan. f. 897, op. 1, d. 86, l. 1.

- A radio message from Minister of Foreign Affairs of the Republic of Azerbaijan Khoyski to the People’s Commissar for Foreign Affairs of Soviet Russia. January 1920. National Archives of the Republic of Azerbaijan. f. 970, op. 1, d. 112, l. 7.

- Russian Revolution and Azerbaijan: Difficult Road to Independence, 1917-1920: monograph/ J. Hasanli – Moscow: Flinta, 2011 (p. 526)

- (ibid. p. 540)

- (ibid. p. 578)

- Azerbaijan Democratic Republic. Baku: “Elm”, 1998, (p. 117)

- (ibid. p. 117)

- A telegram from V.I. Lenin to G.K. Ordzhonikidze about the necessity of taking Baku and cautions in the preparation of the offensive. 17.03.1920. Russian State Archive of Socio-Political History. 85, op. 13, d. 1, l. 1.

- Russian Revolution and Azerbaijan: Difficult Road to Independence, 1917-1920: monograph/ J. Hasanli – Moscow: Flinta, 2011 (pp. 552-553)

- (ibid. pp. 590-591)

- Azerbaijan Democratic Republic (1918-1920). Army. (Documents and Materials). Baku, publishing house “Azerbaijan”, 1998. (p. 274)

- Azerbaijan Democratic Republic. Baku: “Elm”, 1998, (p. 119)

- (ibid. p. 119)

- Shirokorad – The Great River War 1918-1920 / A. B. Shirokorad – Moscow: Veche, 2006 (p. 232)

- Azerbaijan Democratic Republic. Baku: “Elm”, 1998, (pp. 116-119)

- (ibid. p. 119)

- Message from M. Kemal to the Soviet government. 04.1920. Archive of the Foreign Policy of the Russian Federation. f. 04, op. 51, p. 321а, d. 54868, l. 1.

- Azerbaijan Democratic Republic. Baku: “Elm”, 1998, (p. 120)

- Russian Revolution and Azerbaijan: Difficult Road to Independence, 1917-1920: monograph/ J. Hasanli – Moscow: Flinta, 2011 (p. 582)

- (ibid. p. 536)

- Azerbaijan Democratic Republic. Baku: “Elm”, 1998, (p. 120)

- Balayev A. Mamed Emin Rasulzade (1884–1955). Moscow: Flinta, 2009,(pp. 201-202)

- Azerbaijan Democratic Republic. Baku: “Elm”, 1998, (p. 120)

- Azerbaijan Democratic Republic. Baku: “Elm”, 1998, (p. 122)

- Russian Revolution and Azerbaijan: Difficult Road to Independence, 1917-1920: monograph/ J. Hasanli – Moscow: Flinta, 2011 (p. 596)

- (ibid. pp. 597-598)

- Parvin Darabadi. Military and political history of Azerbaijan (1917-1920), Baku 2013(pp. 255-256)

- Darabadi P. The Baku operation of XI Army, Bulletin of the Russian Academy of Sciences/ History, philosophy, law, 1992, № 5, p.34

- Russian Revolution and Azerbaijan: Difficult Road to Independence, 1917-1920: monograph/ J. Hasanli – Moscow: Flinta, 2011 (p. 600)

Be the first to comment at "The April 1920 invasion, the fall of the first republic"