Since ancient times, in order to consolidate their political power, conqueror-states, such as the Sassanids, and later the Arab Caliphate carried out the resettlement policy in the occupied countries. Starting the capture of the Caucasus, Russia has also sought to turn it into an integral part of the empire. In order to consolidate its political power in the mega region, since the late eighteenth century the Russian state carried out the resettlement policy and integrated foreign ethnic, land, language and religious elements – Russians, Germans, Armenians – into the ethno-religious composition of the population of the Caucasus. This infiltration was associated with the colonial policy of the empire. As one of its components, immigration policy pursued certain objectives: to include Christian ethnic groups in the ethnic and confessional scope of inhabitants of the Caucasus, reduce the proportion of indigenous nations, create a non-Muslim confessional foundation. The essence of it was to devour the Caucasus in all respects: politically and ethnically, militarily and economically, ideologically and religiously.

In order to strengthen its southern borders, the empire, at the end of the eighteenth century, transformed the ethno-confessional structure of the population of the North Caucasus. Already during the conquest of this choronym, Russia, which was interested in its soonest conquest, resettled German colonists from the Volga region. Thus, October 27, 1778 a special report “On the resettlement of colonists from the meadow side of the Volga in the line drawn between Mozdok and Azov” was approved by Catherine II. However, until the mid-nineteenth century, this process was spontaneous and at the end of the 1840s only five German colonies have been registered in the North Caucasus.

During the conquest of the North Caucasus, the Russian Empire also conducted Russian colonization. Just in the last quarter of the eighteenth century the Cossack villages were created near Pavlovskaya, Mariinskaya, and Georgievskaya fortresses and as well as the settlements of the Russian peasants (4 thousand people) from the Kursk, Voronezh and Tambov governorships. And after the signing of the Treaty of Jassy (in 1791) the number of Cossacks on the lands of Taman, along the right bank of the Kuban River has reached 25 thousand people. Later, this area was populated by Russian peasants, mainly coming from the Don. In the nineteenth century the Russian colonization of the North Caucasus continued, but its social base was formed by the Little Russian Cossacks.

Germans-separatists became the first Christian settlers in the South Caucasus, natives of the Württemberg kingdom. The Russian government has provided them with benefits and subsidies. However, later, the ruling circles were disappointed in German settlers and found their further stay in the South Caucasus inexpedient, where they were assigned the role of culture-bearers and Christian missionaries. But the actual materials prove the opposite, stressing hard work, punctuality and sobriety of these settlers. Subsequently, the relocation of the Germans had been suspended. But the colonists, who came to the South Caucasus, in particular in the Northern Azerbaijan, have left good memories about themselves, becoming an object of study of certain researchers of the national historiography.

In the first third of the nineteenth century, the Russian Empire populated the South Caucasus with Russians. In that historical period, the social base of Russian colonization consisted of sectarians, but in general, this colonization had no targeted sequence. The rate of quantitative growth of Russians in the South Caucasus until the last third of the nineteenth century did not meet the requirements of the Russian colonization plans, and only at the end of the nineteenth century the Empire began to gradually relocate Orthodox Russian peasants into the region of the central provinces, adhering to the famous theses of the Great Russian ideology: “Russian state power in the Caucasus was there to be truly Russian” and which “could strengthen the power and prosperity of Russia”. As a result of a new wave of Russian colonization in the early twentieth century, 89 resettlement villages formed just in the Mil and Mugan steppes of northern Azerbaijan, and the whole Russian population in the South Caucasus has exceeded 350,050 people.

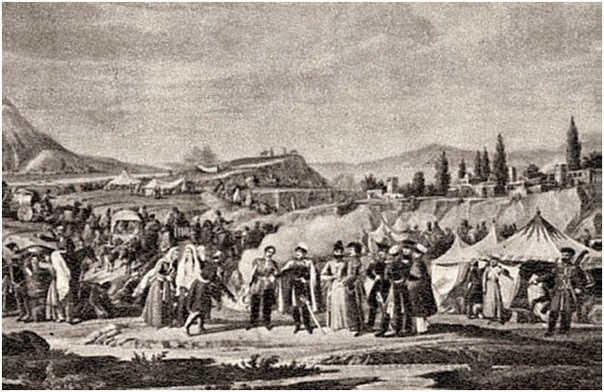

One of the components of the resettlement policy of the Russian Empire was an Armenian colonization. In the first third of the nineteenth century, Russia conducted mass resettlement of Armenians in the South Caucasus and in particular in the northern lands of Azerbaijan. If at the end of the nineteenth century, the apologists of Russian autocracy believed that “Armenians do not provide guarantees of political reliability”, then already during the First Russian-Iranian war (1804-1813) Russian officials, indeed, favored Armenians, believing that “according to uniting Christianity and under the protection of the Russian government, they have in-depth devotion to the Russian dominion for their own benefit” and that Armenians, as Eastern Christians, supposedly are better than others in adapting to the conditions of life in the eastern countries. As a result, after signing the Treaties of Turkmenchay and Adrianople, the tsarist authorities resettled 119.5 thousand Armenians into Northern Azerbaijan. This process continued in the following decades of the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. As a result, the proportion of the Armenian population has increased, reaching 1,208,615 people in the Central Caucasus (excluding Tbilisi and Kutaisi provinces) in the early twentieth century.

Hajar Verdiyeva Doctor of Historical Science

Be the first to comment at "Resettlement policy of the Russian empire in the Caucasus Part II"