The XVIII-XIX centuries were a turning point in the history of the Caucasus. The centuries-old struggle of the leading states of the world for the region ended with the victory of the Russian Empire, which under Peter I turned into a maritime power. Opening a “window” to Europe, the emperor-reformer sought to expand the boundaries of the empire in the southern direction. However, in the beginning of the XVIII century, the matter of access to the Black Sea was closed for Russia and Peter I turned his attention to the Caucasus.

As a result of the Caspian campaign of Peter I (1722), the western shore of the Caspian Sea had been conquered, and the Istanbul Treaty (1724) consolidated these Russian conquests in the international system. However, regime of “bironovshchina”, established in Russia after the death of the Emperor, not interested in the Caucasus issue, signed Rasht (1732) and Ganja (1735) treaties and abandoned Peter’s conquests. But the Empress Elizabeth Petrovna purposefully continued the work of her parent. During her reign, the Black Sea problem and the issue of the Caucasus has become a top priority of Russian foreign policy. Over time, already under Catherine II, after the Russian-Ottoman war of 1768-1774, the Treaty of Küçük Kaynarca (1774) has strengthened Russia’s position in Crimea and on the Azov coast, completely incorporating Kabardia into the Russian Empire, thus expanding the scope of its influence in this horonime.

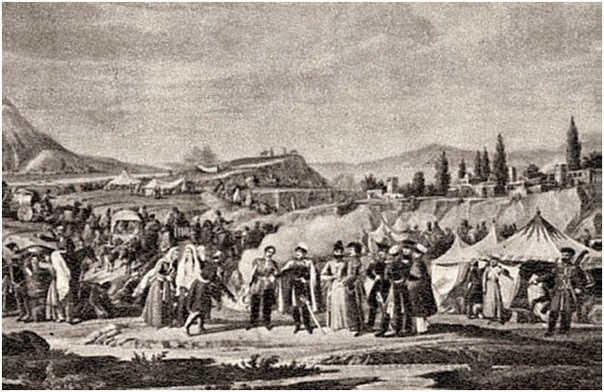

The struggle for the Caucasus continued even after the ratification of the Treaty of Küçük Kaynarca. In 1783, Crimea became part of Russian, and it gained dominance in northern Black Sea Coast. In the same year it strengthened its position in the South Caucasus, by concluding the Treaty of Georgievsk with the ruler of the kingdom of Kartli-Kakheti Heraclius II, who recognized its patronage and abandoned his right to independent foreign policy. With the accession of the Kingdom of Kartli-Kakheti in 1801, Romanov’s Russia, without hiding its true intentions, set foot on Azerbaijani soil. The Qajars, which tried to oust Russia from the mega-region with the support of Western countries, began military operations, but the two Russian-Iranian wars ended with the victory of the Russian Empire, and after the Treaty of Turkmenchay (1828) the autocracy included the South Caucasus to its political and geographical space.

To subdue the Caucasus, the tsarist government has been implementing a colonial policy already in the process of conquests, the essence of which was the assimilation of the local population and the transformation of the mega-region into an integral part of the Russian Empire. The main components of this strategic course were the Christianization and immigration policies.

While launching a campaign to conquer the Caucasus, Russia has clearly realized that the captured Muslim region will be the weak link in the country, because confessionally alien population will not tolerate foreign invasion. The ruling circles of the Empire clearly understood: a recalcitrant region can be controlled not at the point of a bayonet, but with the help of religious rapprochement between mother country and colony, to be exact – the infiltration and enforcement of Christianity. Therefore, at the end of the eighteenth century, they created the Ossetian Theological Commission in Tbilisi, defining its main task as the spread of Orthodox Christianity among the Muslims of the Caucasus for its rapprochement with Russia. At the same time, representatives of Non-Orthodox faiths were also engaged in missionary activity in the Caucasus. Society of Scottish Missionaries, established in Astrakhan, June 22, 1815 by decree of the Minister of Internal Affairs, conducted their activities in a narrow geographical area, in the coastal strip of the Caspian Sea, and its main objectives were spreading and preaching of the Gospel on the mentioned territory.

Along with Scottish Christian missionaries, Basel Christian missionaries also operated in the Caucasus, activities of which covered the territory between the Black and Caspian seas. Basel Evangelical Society has set the goal before missionaries: to spread Christianity in the Caucasus. However, the activities of foreign Christian missionary societies did not produce the expected results. Indigenous peoples of the Caucasus have not shown interest in Christianity (except for some cases) that did not meet the policy of Christianization of the Russian Empire in the Caucasus. As a result, its official representatives concluded: missionaries sent by Edinburgh and Basel societies do not benefit the Power in enforcing and spreading Christianity on the conquered outskirts. The ruling circles of Russia, not taking into account the mentality of the indigenous population of the Caucasus, where Islam was the determining factor of the identity of the people of this mega-region, created a “Society for the restoration of Orthodox Christianity in the Caucasus”, and the Ossetian Theological Commission was abolished due to inefficiency. Russian Empire, deliberately spreading Christianity in the Caucasus and relying on Orthodoxy, entrusted the new society with the task of restoration and maintenance of the ancient Christian churches and monasteries in the Caucasus, construction of new churches, parochial schools, and distribution of the Books of Holy Scripture in there.

Source: The Caucasus and Globalization. Issue №5 / Volume 1/ 2007 pp. 152-160

Hajar Verdiyeva Doctor of Historical Science

Be the first to comment at "Resettlement policy of the Russian empire in the Caucasus Part I"