A brief history of the existence of the First Republic was the beginning of an active building of the national army. The process was launched in the summer of 1918. In accordance with the Decree of the interim government of Azerbaijan of June 26, 1918, the Muslim Corps was renamed “Detached Azerbaijani corps” (1). General S. Mehmandarov was appointed a Minister of Defense, General A. Shikhlinski was appointed a deputy Minister of Defense, and M. Sulkevich was appointed a chief of the headquarters. The process of organizing and arming the army was difficult. By the beginning of 1920, the army consisted of “the 1st (headquarters in Ganja) and the 2nd (Baku) Infantry Divisions, each of which had three regiments (1000 to 1700 people, depending on the effectiveness of recruitment), and one Cavalry division, composed of four hundred strong Tatar, Karabakh and Sheki cavalry regiments, as well as the Kurdish Cavalry Division. In addition, the army included two artillery brigades, light artillery division, police reserve regiment and irregular units throughout the country” (2). The total authorized strength of troops was estimated at about 30 thousand people (3).

The March uprising of 1920 was a serious test for the units of the national army. It is worth noting that the reports of the existence of a threat of take-over of Shusha, Askeran and Khankendi by the Armenian armed units were received back in January (4). In order to neutralize those attempts, March 15, 1920, State Defense Committee adopted a resolution suggesting to “take several strategic points in Karabakh by military forces to impede the movement of Armenian military units and their merge with the Armenians of Karabakh and Zangezur, as well as to create a favorable strategic environment in case of a possible uprising of the Armenians of Nagorno-Karabakh” (5). The measures taken were not in vain. During the night of 22 to 23 March, when the Azerbaijani population was traditionally celebrating Novruz holiday, Armenian revolt broke out in Karabakh. Describing the events of the March uprising, the Azerbaijan newspaper reported: “On the night of 22 to 23, the cities of Shusha, Khankendi, Askeran and Terter, where we have military units, were simultaneously treacherously attacked by the Armenian armed forces. In Askeran, Armenian armed forces attacked the 50-person unit that was sleeping, captured them and took positions of Askeran. In other places, Armenian troops were repelled suffering losses” (6).

The March uprising of 1920 was a serious test for the units of the national army. It is worth noting that the reports of the existence of a threat of take-over of Shusha, Askeran and Khankendi by the Armenian armed units were received back in January (4). In order to neutralize those attempts, March 15, 1920, State Defense Committee adopted a resolution suggesting to “take several strategic points in Karabakh by military forces to impede the movement of Armenian military units and their merge with the Armenians of Karabakh and Zangezur, as well as to create a favorable strategic environment in case of a possible uprising of the Armenians of Nagorno-Karabakh” (5). The measures taken were not in vain. During the night of 22 to 23 March, when the Azerbaijani population was traditionally celebrating Novruz holiday, Armenian revolt broke out in Karabakh. Describing the events of the March uprising, the Azerbaijan newspaper reported: “On the night of 22 to 23, the cities of Shusha, Khankendi, Askeran and Terter, where we have military units, were simultaneously treacherously attacked by the Armenian armed forces. In Askeran, Armenian armed forces attacked the 50-person unit that was sleeping, captured them and took positions of Askeran. In other places, Armenian troops were repelled suffering losses” (6).

Urgent measures have been taken to suppress this danger. March 24, 1920, by order of the Minister of Defense General Mehmandarov, Chief of Staff of Azerbaijani Army Major General Salimov (appointed to this position on March 2) was urgently sent to Karabakh. From Agdam, Salimov reported the following on the situation in Karabakh: “According to intelligence reports, Armenians have consolidated a regular infantry regiment under Colonel Kazarov in Gerus. Dro has 7 thousand partisans in Zangezur district. Partisans of Deli Kazar, consisting of 4 thousand armed men together with local Armenians, operate in the area of Askeran, Bruj” (7). He didn’t forget to make a personal assessment of the developments describing everything that happened as an “unspoken war” (8). In general, at the start of “Askeran Operation “, Salimov assessed the condition of Azerbaijani troops on the front line as “sustainable” and added “Waiting for regroupment of sent reinforcements to go to a decisive offensive” (9).

The offensive of the Azerbaijani troops, which began on April 3, turned into a major success resulting in liberation of Askeran and regaining control over Khankendi and Shusha. General Salimov wrote in detail about it in his report dated April 5: “In the direction of Shusha we took Dashbashi, Engidzha, Mehtikend, Kayabashi, Baludzha and Khanazakh. In the 16th hour, troops were concentrated in Khankendi, Shusha-Khankendi road is under fire from Shushakend and Dashkend. I still assume to pass Shusha on 5th”, “involvement of three regular battalions in battle of April 3 is confirmed. It is clear from the correspondence that there are other units. Deli Kazar, who called himself Commander in Chief of the Karabakh forces, was killed in a circle trench in the village of Kurd-Khanabad. This, apparently, greatly undermined the spirit of the Armenians” (10). Already in Shusha, on April 5, General Salimov reported “By evening of 4th, the villages of Kyatik, Aran-Zamin, Nakhchivanik were taken, a column left for Malibekli” (11). Meanwhile, in another part of frontline (in Terter direction) Talish village was liberated on April 7 (12). After persistent four-day battles on the front lines of Shusha, Keshishkend and Shushikend were taken on April 12, this was reported from Askeran by General Salimov in his report dated April 14. (13)

Despite the successes, achieved during the April battles in 1920, there was a number of circumstances that complicated the situation of Azerbaijani units in Karabakh and hindered their advance in some parts of the front (Jabrail, Tartar), as well as the organization of the offensive in the direction of Zangezur (this offensive was supposed to begin around April 20). Describing the problems of the Azerbaijani units, General Salimov reasonably noted, “The main drawback is the lack of experienced officers, at least as battalion commanders. I personally have to direct and move not only the regiments and battalions, but even companies” (14). For this reason he has requested an expedited transfer of officers who received at least a three-week training. Obstacles have also been created by local Armenian population, which, according to Salimov, “formed a number of units, which organize night raids to one or another Muslim village, burn them and then go to the mountains” (15). Not always well-organized second-line logistic support played a role. Salimov wrote about it: “I cannot handle conducting operations, personally leading battles and simultaneously taking care of the delivery of food, combat and sanitary supplies” (16). The intensified Bolshevik agitation played its part in reducing combat capability of military units, which led to desertion and insubordination to commands of superior officers. Assessing that circumstance, the historian R. Mustafazade wrote, “It is important to emphasize that desertion in some units was not of a passive but an active nature – the soldiers remained in service, but they obeyed the orders not of the War Ministry, but of their commanders sided with the Bolsheviks and acted against the lawful government” (17). The incursion of the military units of the Soviet Russia into Azerbaijan and capture of Baku has resulted in the Minister of Defense, General Mehmandarov, being forced to abdicate his authority and transfer it to the new government. It has definitively put an end to the further organization of troops and the offensive in the direction of Zangezur.

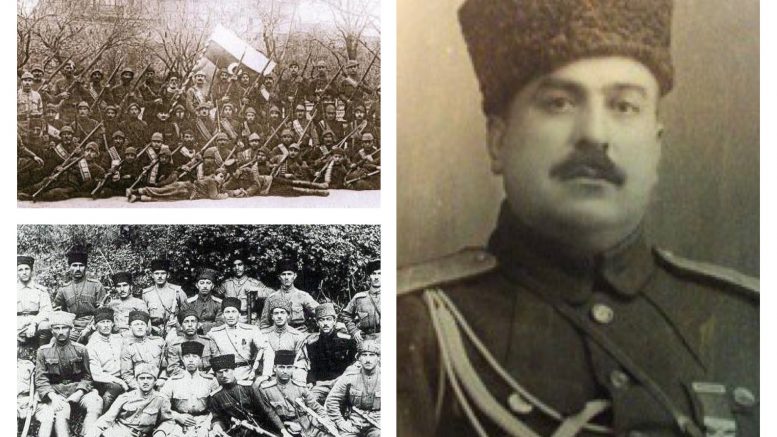

In conclusion, it should be said that despite all the hardships and difficulties that have hit a newly built army, officers and soldiers demonstrated exemplary courage defending their homeland, sparing no effort, expense or health. An example of this would be the words of

General Salimov

himself, said a few days before the Russian invasion, “I’m aware of everything perpetrated in Karabakh and take all measures which I find necessary for the conditions of the situation. Believe me, I don’t spare myself and in the direction where I am and personally command, the enemy won’t take us by surprise” (18).

The further fate of Salimov was no less tragic. A military historian S. Nazirli wrote about the last days of this talented officer, who was one of those who stood at the origins of the formation of a national army: “After all these false accusations, December 30, 1920, at 10:30 the Bolsheviks executed General Habib bey Salimov by shooting. One of the paragraphs of the decision made by “troika” was the confiscation of General’s property. What did General Salimov own? The documents indicate: Habib bey Salimov, 39, single. Lives with his brother, has two dessiatinas of land and three dessiatinas of land on country side, inherited from his father. That’s all.” (19).

I would also like to emphasize that distraction of capable units of ADR army from the northern border to the western direction facilitated the Russian occupation of Azerbaijan. Actions of Armenian forces in Karabakh facilitated the Russian occupation of Azerbaijan, thus creating favorable conditions for the occupation of the Armenian Republic and Georgia in 1921.

Used sources:

- The Azerbaijan Democratic Republic (1918-1920). Army. (Documents and Materials) – Baku, publishing house “Azerbaijan”, 1998. (p. 13)

- Mustafa Zadeh R.S. The Two Republics. Azerbaijani-Russian relations in 1918-1922 n: -M, 2006. (p. 67).

- p. 68

- The Azerbaijan Democratic Republic (1918-1920). Army. (Documents and Materials) – Baku, publishing house “Azerbaijan”, 1998. (p. 244)

- p. 251

- p. 266

- p. 277

- p. 279

- p. 289

- p. 293

- p. 293

- p. 294

- p. 312

- p. 314

- p. 318

- p. 310

- Mustafa Zadeh R.S. The Two Republics. Azerbaijani-Russian relations in 1918-1922 n: -M, 2006. (p. 101).

- The Azerbaijan Democratic Republic (1918-1920). Army. (Documents and Materials) – Baku, publishing house “Azerbaijan”, 1998. (p. 319)

- Shamistan Nazirli, Caspiy. – 2011 – February 5 – p. 9 –

Be the first to comment at "The March uprising in Karabakh (1920) and its implications for the South Caucasus"