Having proclaimed the Azerbaijan Democratic Republic, the leaders of the first republic faced a number of serious problems impeding the full implementation of intended political and social reforms. One such problem was the presence of “territorial dispute” with the neighboring republics of Georgia and Armenia. This issue was particularly acute in disputes with Armenia (Araratian Republic), which often rose to the level of armed conflict involving casualties. “Karabakh” was one of those disputed territories between the ADR and Armenia.

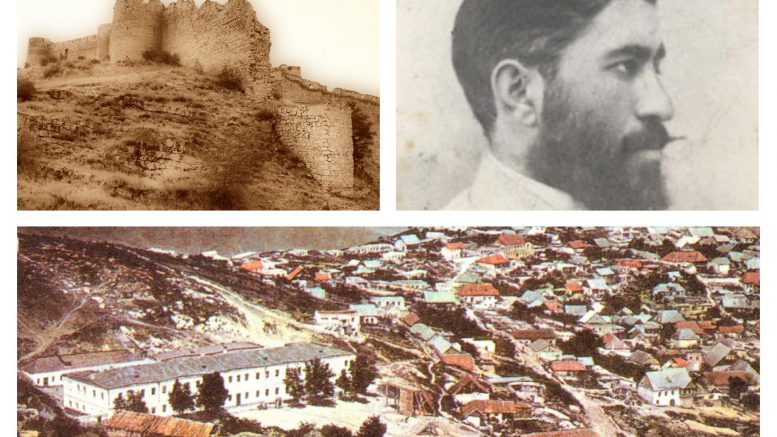

At the time of the declaration of the two republics, there was no separate administrative unit called “Karabakh”. Therefore, in this case, it would be correct to speak of “Geographic Karabakh”, territory that was part of Elisabethpol Governorate and consisted of four uyezds (administrative units): Shusha, Zangezur, Javanshir and Jabrayil (Karyagin). All four administrative units were established in stages, since the mid-19th century, in place of the “Karabakh Province” abolished in 1840 (which, in turn, was created in place of the “Karabakh Khanate” that was abolished in 1822).

Just before the proclamation of the ADR the Azerbaijanis continued to make up a relative majority in Karabakh. According to the “Caucasian calendar for 1917”, the numerical ratio between Azerbaijanis and Armenians in the above mentioned uyezds was 315 thousand Azerbaijanis (Tatars) against 242 thousand Armenians. By analyzing this data, a staff member of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the ADR, A. S. Shepotyev, has come to the conclusion that the number of the Armenians living in Karabakh was exaggerated. He argued that the number of Muslims not subject to conscription is much higher than indicated in the statistics and that the number of Karabakh Armenians has increased due to those emigrating at the time from Karabakh to other cities. Shepotyev concluded that the number of Armenians living in Karabakh is 170 thousand people, and the number of Azerbaijanis is 415 thousand people.

The ADR leaders entered the diplomatic fray over Karabakh immediately after the declaration of independence. One of the first steps was an agreement (during the Batumi Conference) to concede the city of Erivan (today’s Yerevan) to become a political center for Armenians (members of national council called the concession of Erivan a “necessary evil”, the critical state of the government and the need for liberation of Baku in many ways played a crucial role in making this decision), provided that Armenians will give up their claim to Karabakh. Time has shown that it did not have the desired effect. As in July 1918 F. K. Khoyski wrote to Mammad Amin Rasulzadeh, who was in Istanbul “…if the Armenians claim Karabakh, then you should refuse to transfer Erivan and part of Kazakh uyezd to them”. The situation in Karabakh has been stabilized by the end of summer. According to the “Treaty of Friendship”, concluded between the ADR and the Ottoman Empire, the fourth paragraph of which provided the ADR an opportunity to ask for military assistance if necessary, and they immediately took advantage of it. By order of Nuri Pasha, on August 10, troops were sent to Karabakh in order to restore order. After the signing of the Armistice of Mudros and the withdrawal of Turkish troops, Armenians re-launched attacks against Azerbaijanis in Karabakh.

Turmoil and chaos that erupted in Karabakh following the withdrawal of Turks, has forced the ADR leaders to resort to drastic measures. On January 15, 1919, having coordinated with the British command, Dr. Khosrov bey Sultanov was temporarily appointed governor-general of Zangezur, Shusha, Javanshir and Jabrayil uyezds. The British side stated that it is important to emphasize that the decision on whether those areas belong to one or another country must be made at the peace conference. Local National Council of Armenians found the appointment of Sultanov as governor-general of Karabakh “insulting”, stating that “Armenian Karabakh cannot come to terms with such fact”.

Given the existing situation, Sultanov, already in the first months of his appointment, wrote to the Prime Minister N. Yusifbeyli about “the necessity of subordinating military units to him, for a peaceful resolution of the Armenian question in Karabakh…”, justifying it as follows, “…paragraph 6 of the official British proclamation, which states that any movement of military units should be reported to the British mission in Shusha, was also adopted by our government. This paragraph cannot be implemented without the subordination of military units to local supreme authority, because, with more than unsatisfactory performance of telegraph lines, communication with the Minister of War is almost impossible, at best, pointless…”. Responding favorably to that request, Yusifbeyli informed S. Mehmandarov about it: “The Governor-General Dr. Sultanov, reporting on the foregoing and acknowledging the situation as being extremely worrisome, finds the presence of 2000-strong army of askars (soldiers) in Karabakh necessary for the final elimination of the Karabakh issue…”. This proposal was approved by the British administration as well, which ordered that “Military units located within the Karabakh Governorate General act with the knowledge and consent of the Governor General”. The strengthening measures taken by Sultanov have not been in vain. In the early summer of 1919, another round of tension between Armenians and Azerbaijanis turned into an armed clash. Sultanov on the clashes of June 4-5: “Due to nomads coming through, I have set up reinforced outposts… all checkpoints around Shusha are taken, in order to prevent armed men from entering Shusha… The restless elements of Armenian population did not like it, apparently led by the Armenian National Council, and on June 4 they first attacked the post occupied by our askars on “Uch-Mykh”. By the beginning of the second day the shootout was stopped. Victims from our side – 3 killed, 4 wounded”. “Nomads, forced to temporarily change the direction of travel passing near the Armenian village of Gaybaly kend, came under fire. In turn, they were forced to clear their way for safe passage. The village was burned, there are killed and wounded on both sides. The refugees left without the head of the family are fully supported”, “…the British promised to detain and expel, and indeed detained and expelled Ishkhanyan, Avetisyan and Tumanyan from Shusha and out of Azerbaijan…”. In turn, Armenians accused Sultanov of “organizing massacres and pogroms in the Armenian neighborhoods”, and his brother Sultan bey Sultanov of destroying and burning Gaybaly. Although after the establishment of peace the leaders of the Armenian neighborhoods of Shusha wrote Sultanov a letter of apology.

An effort towards a peaceful settlement of Karabakh conflict was made in the summer of 1919. At the 7th Congress of the Armenians of Karabakh an “interim agreement between the Armenians of Nagorno-Karabakh and Azerbaijani government” was signed. The second paragraph of the agreement stated: “Mountainous part of Karabakh – Shusha, Javanshir and Jabrayil uyezds (Dizak, Varanda, Khachen and Dzharabert), populated by Armenians, consider themselves temporarily within the Republic of Azerbaijan” (Until the resolution of this issue at the peace conference). Armenians of the mountainous part of Karabakh were provided national-cultural autonomy. Azerbaijan got the opportunity to have garrisons in Shusha and Khankendi (movement of Azerbaijani military units in the Armenian part of the Nagorno-Karabakh could be done with the consent of 2/3 of the members of the Council). Armenians, who left Karabakh for political reasons, have returned to their homes and so forth. Armenians themselves justified this decision by “being isolated from Armenia”, “insufficient number of military equipment”.

Head of the General Staff of the ADR Army, Mohammed Sulkevich (Lithuanian-Tatar), shared with Sultanov his thoughts on this agreement: “The peaceful resolution of the Karabakh conflict makes me think that the annexation of Zangezur uyezd will happen without armed struggle…”, but also added “…such favorable conditions may not last permanently, and we must prepare for the worst”. Sulkevich was not wrong in his thinking. In February 1920, Sultanov wrote Mehmandarov about the situation in Karabakh: “lately, Armenians, despite the assurances of the National Council and the Council led by me, behave disloyal, succumbing to the propaganda of Ararat agents… They are currently preparing everywhere”. The refusal of the eighth congress of Armenians to accept Sultanov’s proposal on “Karabakh’s complete inclusion within Azerbaijan” is also proof of that. At the same time the congress accused him of the murder of hundreds of Armenians and of its intention to resort to appropriate protective measures. In response to those statements, Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the ADR sent a note of protest, rejecting the accusations.

The logical result of this activity of Armenians in Karabakh was the March uprising of 1920. Sultanov wrote in this regard: “On March 23, starting from two-thirty at night, Armenians with growing force attacked our military unit in Khankendi. At the same time Armenians began launching attacks in Shusha. The attacks are repelled; shootings are taking place in the area”. Despite his difficult situation, courage and dedication shown by Sultanov during the March uprising deserves respect. We can see it from his following report: “Shusha and Khankendi garrisons are at great risk from the Armenians of Zangezur, tirelessly seeking to invade Shusha and Khankendi using the combined forces of Karabakh, taking advantage of the closure of Askeran. I ran out of ammo that was at my disposal. The situation in the city and Khankendi is closely dependent on the operation of Askeran, and any delay of this operation will cause a very sad complication for the entire Karabakh”.

In conclusion it is worth saying that the battle which took place in Karabakh in March-April 1920 will be remembered by its dramatic nature and courage displayed by the national military units. Despite the successful advance of our troops in Karabakh and taking Askeran, Shusha, Khankendi, the complete suppression of enemy’s resistance and launching military offensive on Zangezur was complicated by a number of factors, which include: shortage of manpower (professional military officers), not always well-organized supply, guerrilla raids on army units, Bolshevik propaganda among the soldiers of the national army. All that was happening against the backdrop of difficult international situation in which the ADR found itself, ended with the occupation of Azerbaijan by Soviet Russia. Thus, the fate of Karabakh was destined to be decided under the new Soviet rule…

Be the first to comment at "The Karabakh issue in 1918-1920"